Heb. 8:6 - "based on better promises"

The Old Testament was based on earthly promises that pertained to this life (prosperity, posterity, longevity, etc). The New Testament, however, is based on better heavenly promises that pertain to a life eternal that never grows old, to an inheritance that never fades (Heb.8:6).

It is very important for a Christian to understand the difference of life under the Old Covenant and life in the New Covenant. The New Covenant comes with the promise of the Holy Spirit, of eternal life, of eternal inheritance, of eternal rest, and much more.

Do Not Quench the Spirit

"Do not quench the Spirit." (1Thess.5:19)

The Spirit is quenched by:

1. Ignoring the voice of the Spirit (Heb.4:7)

2. By careless talk (Eph.4:29)

3. By lovelessness, bitterness, anger, and lack of forgiveness (Eph.4:30,31)

4. By willful sinning and not esteeming highly the value of Christ's blood (Heb.10:29)

5. By opposing the work of the Spirit (Matt.12:31,32).

- When one hardens his heart against the voice of the Spirit, the Spirit will stop striving with him. It leads to abandonment (Rom.1:21-26)

- When one piles up careless and corrupt talking, his fountain is defiled and his rudder has turned his ship to self-destruction (James 2:1-6). Instead, one should pray in the Spirit and sing spiritual hymns and encourage others in Christ (Eph.5:18-20)

- When one cannot love his brother and sister, hatred blinds his eyes (1Jn.2:11), and he doesn't have the life of God.

- When one continues to willfully sin and has no esteem for the blood of Christ, he insults the Spirit of Grace (Heb.10:29)

- When one speaks against the Holy Spirit and knowingly rejects the work of the Spirit, there is no forgiveness for him anymore.

Acts 3:6 Christ didn't leave with us silver and gold

"Silver and gold have I none..." (Acts 3:6)

How often the things that we seek after are not what Christ left for us when He ascended to heaven! How attractive is a religion that promises silver, gold, good job, land, house, prosperity, and all worldly things! Jesus didn't leave any of such things for His disciples. But, these are what the modern Judas Iscariots are trying to sell Jesus off for; for filthy lucre that is good for none. And, no wonder only Judas got some silver out of Jesus, by betraying Him with a kiss. He had to sell Him. In history past, the Church sold relics and indulgences promising people a place in heaven; in the present scenario, they invite people to "sow seed" of money to reap more money; testimonies are used as ideal adverts that take off the eyes from the real Jesus of the manger onto some other Jesus who makes people forget that they are pilgrims and travelers in this rapidly degenerating world. But, what does Jesus want us to pursue? The very things He left for us: the Father's Name (Jn.17:6), the Father's Word (17:14), His Authority and Power of the Holy Spirit (Lk.10:19; Acts 1:8). Are we pursuing the true spiritual riches of Christ? Or are we following a false Christ, even the anti-Christ?

The Wheat Must Die To Bear Fruit (Jn.12:24)

"Unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it produces much grain." (Jn.12:24)

There comes a time when you have to stop being fruit and start bearing fruit; but, that only comes by dying to the compulsions that hinder us from falling into the bosom of God, the Ground of our soul.

There comes a time when you have to stop being fruit and start bearing fruit; but, that only comes by dying to the compulsions that hinder us from falling into the bosom of God, the Ground of our soul.

God and Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ (2Cor.1:3)

"Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ" (2Co.1:3)

~The New Testament, after the Cross, no longer addresses God as the "God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob", since that term applied only to those under the Old Covenant. Through the Seed, the Son of Promise, Jesus, we are brought into a New Covenant that He made with His own blood. Now, God is known to us as the "God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ." His sonship is according to the Spirit; His priesthood according to the order of Melchizedek. Therefore, we no longer have confidence in the flesh, in genealogies or ethnicities; we are children of God by faith alone in Jesus. New wineskins for new wine; the new can never be put into the old..

~The New Testament, after the Cross, no longer addresses God as the "God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob", since that term applied only to those under the Old Covenant. Through the Seed, the Son of Promise, Jesus, we are brought into a New Covenant that He made with His own blood. Now, God is known to us as the "God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ." His sonship is according to the Spirit; His priesthood according to the order of Melchizedek. Therefore, we no longer have confidence in the flesh, in genealogies or ethnicities; we are children of God by faith alone in Jesus. New wineskins for new wine; the new can never be put into the old..

God is Our Father

God is our Father.

1. A Caring Father (Mat.6:32)

2. A Chastening Father (Heb.12:6)

3. A Comforting Father (2Cor.1:3)....

Vedic Worship

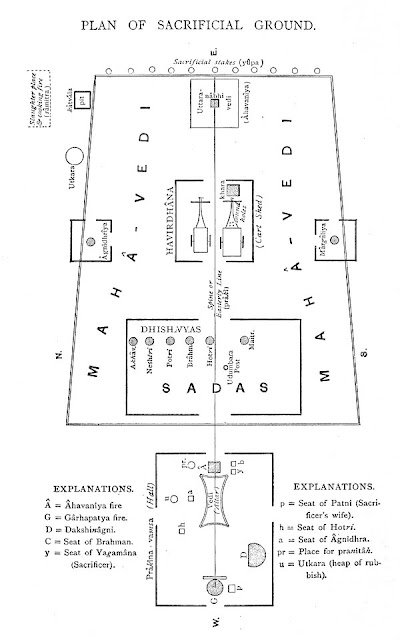

There is no indication of temples in the Vedic period. Also, there is no record of idol worship in the Vedas. However, there is mention of altars. The altar (vedi) was considered to be earth’s extremest limit; and sacrifice, the navel of the world (RV.1.164.35). One of the altars was made to sit on the earth, was considered to be eye-shaped, and the sacrifice was directed sun-ward. Trimmed ladle was used to pour oil into the altar’s fire (RV.6.11.5). However, there were altars of various other shapes as well.

B.G. Sidharth suggests a possible “connection between the fire altars in Turkmenistan (Togolok) and Afghanistan (Dashly) and the Harappan civilization, particularly Kalibangan, where there are seven fire altars, and also with the Harappan seal showing worship at a fire altar with seven accompanying deities.”[1] He tries to reconcile these archaeological discoveries with the concept of the seven fires in the Rig Veda which he considers to be purely astronomical and connected with the myth of the Pleiades or Krittika and the seven stars of the Great Bear or Sapta Rishi (the Seven Sages).

For the Vedic priests, the altar was not just a random structure; it had cosmic relationship—it was earth’s extremest limit, the sacrifice was the center of the world. Meticulous calculations were made to assure the positioning of it. Astronomical, geometrical, and mathematical calculations came into play when situating and constructing an altar. Some have suggested intricate astronomical relations in the choice of the number of stones and pebbles to be placed around the altar.[2] The A.B. Keith notes that the altar was arranged to represent earth, atmosphere, and heaven, and the same arrangement is devised in the fire-pan.[3] There were elaborate procedures of determining the shape and size of altars, setting up of fire; various kinds of sacrifices and offerings; timings for setting up the altars and performing the sacrifices, etc. For instance, the Garhapatya altar was round whereas the Ahavaniya altar was square. There were new moon and full moon sacrifices, four-month or seasonal sacrifices, first-fruit sacrifice, pravargya or hot milk sacrifice, and animal sacrifice.[4] One important sacrifice was the Soma sacrifice in which animals like goats and cows were sacrificed to various deities.[5]

The chief priest was Agni (Fire). Since Fire is kindled by mortals and assumes an immortal nature, it is considered to be the mediator between mortals and immortals; it carries the sacrifices to the gods and draws the gods to men (RV.1.1.1-3). Agni is considered the sapient-minded priest (1.1.5), the dispeller of the night (1.1.7), the ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, and the radiant one (1.1.8). Therefore, utmost care was taken in kindling the sacrificial fire.

[1] B.G. Sidharth, The Celestial Key to the Vedas: Discovering the Origins of the World's Oldest Civilization (Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1999), p.101

[2] M. I. Mikhailov, N. S. Mikhailov, Key to the Vedas (Minsk: Belarusian Information Center, 2005), p.201

[3] A.B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1925), p.466

[4] Ibid, pp.313-335

[5] Ibid, pp. 326-332

B.G. Sidharth suggests a possible “connection between the fire altars in Turkmenistan (Togolok) and Afghanistan (Dashly) and the Harappan civilization, particularly Kalibangan, where there are seven fire altars, and also with the Harappan seal showing worship at a fire altar with seven accompanying deities.”[1] He tries to reconcile these archaeological discoveries with the concept of the seven fires in the Rig Veda which he considers to be purely astronomical and connected with the myth of the Pleiades or Krittika and the seven stars of the Great Bear or Sapta Rishi (the Seven Sages).

For the Vedic priests, the altar was not just a random structure; it had cosmic relationship—it was earth’s extremest limit, the sacrifice was the center of the world. Meticulous calculations were made to assure the positioning of it. Astronomical, geometrical, and mathematical calculations came into play when situating and constructing an altar. Some have suggested intricate astronomical relations in the choice of the number of stones and pebbles to be placed around the altar.[2] The A.B. Keith notes that the altar was arranged to represent earth, atmosphere, and heaven, and the same arrangement is devised in the fire-pan.[3] There were elaborate procedures of determining the shape and size of altars, setting up of fire; various kinds of sacrifices and offerings; timings for setting up the altars and performing the sacrifices, etc. For instance, the Garhapatya altar was round whereas the Ahavaniya altar was square. There were new moon and full moon sacrifices, four-month or seasonal sacrifices, first-fruit sacrifice, pravargya or hot milk sacrifice, and animal sacrifice.[4] One important sacrifice was the Soma sacrifice in which animals like goats and cows were sacrificed to various deities.[5]

The chief priest was Agni (Fire). Since Fire is kindled by mortals and assumes an immortal nature, it is considered to be the mediator between mortals and immortals; it carries the sacrifices to the gods and draws the gods to men (RV.1.1.1-3). Agni is considered the sapient-minded priest (1.1.5), the dispeller of the night (1.1.7), the ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, and the radiant one (1.1.8). Therefore, utmost care was taken in kindling the sacrificial fire.

Shatapatha Brahmana

The Shatapatha Brahmana, a part of the White Yajur Veda, dated between 700 BC and 300 BC, elaborates details of the various rituals used in Vedic worship. The name Shatapatha means “hundred paths”. The Brahmana contains portions that may have been orally transmitted through generations before committed to writing about 300 B.C. It is a valuable source of information regarding the thought and life of the Vedic people. Some notable points are as follows:- The gods and Asuras sprung from Prajapati and were both soulless mortals until the gods decided to place the immortal element of fire (Agni) within themselves, thereby becoming immortal (2.2.2.8-14).

- The term Upavas for “fasting” is given a rationale. Upa means "near" and vas means "abide" or "dwell". It is stated that on the day of fasting (upavas), the gods betake themselves to the house of the sacrificer, who would be offering sacrifices of food for the gods to eat. Therefore the day is called upavasatha (or the day of fasting). The rationale behind this fasting is that it is improper for the host to eat before the guests, staying in his house, have eaten; "how much more would it be so, if he were to take food before the gods (who are staying with him) have eaten: let him therefore take no food at all." (1.1.1.7-8). However, the sacrificer is permitted to eat plants and fruits from the forest since there is no offering made of things from the forest, and “that of which no offering is made, even though it is eaten, is considered as not eaten.” (1.1.1.9).

- Brahman is a general name for priests, and there were brahmans also among the Asuras (1.1.4.14).

- The food of the gods is amrita (ambrosia, or not dead), for they are immortals; therefore, rice must be grinded (killed), and then bestowed with immortal life before offering to the gods. Sacrifice, thus, involves the concept of death and immortality (1.2.1.19-22).

- In a sacrifice, the animal or grain being offered dies; however, by giving dakshina to the priest, one invigorates the offering, making it successful (2.2.2.1-3).

- Anyone who makes an offering without giving dakshina (gift to the officiating priest) gets sins wiped off on self (1.2.3.4).

- Rice and barley are ordained as the five-fold animal sacrifice for two reasons: (a) the gods first offered a man as the sacrifice, but the sacrificial essence left him and entered a horse; they offered the horse, the essence left the horse and entered the ox; they offered the ox, but the essence left it and entered the sheep; they offered the sheep, but the essence left it and entered the goat; they offered the goat, but the essence left it and entered the earth; so, they digged in the earth and found it in the form of rice and barley (1.2.3.6-7). (b) The rice-cake, as rice-meal is the hair; when water is poured on it, it becomes skin; when mixed, it becomes flesh; when baked, it becomes hard as bone; and when taken off the fire and sprinkled with butter, it changes into marrow. "This is the completeness which they call 'the fivefold animal sacrifice.' (1.2.3.8).

- Ghee or clarified butter is an important part of the sacrificial rite; it is likened to a thunderbolt (3.3.1.3).

- The sacrifice is the representation of the sacrificer himself (1.3.2.1).

- The altar is compared to a woman of honor who must be clothed in the presence of gods and priests. The altar represents the earth, and the barhi grass with which it is covered represents the plants fixed firmly on the earth (1.3.3.8-10).

- Only Brahmans, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas were considered able to sacrifice (3.1.1.9).

- The housewife (patni) participates in the sacrificial rite (1.2.5.21; 3.4.1.6).

- The one who wishes to perform the rite of consecration must shave his hair and beard and cut his nails because that part of the body where water does not reach is considered impure (3.1.2.2).

- Elaborate measurements are given for the construction of the altars, with rationale for each measurement in the Brahmana.

- Breath is declared to be the one God, of whom the myriads are just powers, proceeding first as one and half Wind, then the three world where all gods dwelt, and then into thirty three, and three hundred and three and three thousand and three (11.6.3.10).

- The world of the fathers is differentiated from the world of the gods (1.9.3.2). The sacrifice aims to go to the world of gods (1.9.3.1).

[1] B.G. Sidharth, The Celestial Key to the Vedas: Discovering the Origins of the World's Oldest Civilization (Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1999), p.101

[2] M. I. Mikhailov, N. S. Mikhailov, Key to the Vedas (Minsk: Belarusian Information Center, 2005), p.201

[3] A.B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1925), p.466

[4] Ibid, pp.313-335

[5] Ibid, pp. 326-332

Vedic Theology

|

| Max Mueller (1823-1900) |

Five thousand years ago, or, it may be earlier, the Aryans, speaking as yet neither Sanskrit, Greek, nor Latin, called him Dyu patar, Heaven-father.

Four thousand years ago, or, it may be earlier, the Aryans who had travelled southward to the rivers of Penjab, called him Dyaush-pita, Heaven-father.

Three thousand years ago, or, it may be earlier, the Aryans on the shores of the Hellespont, called him Ζευς πατηρ [Zeus pater], Heaven-father.

Two thousand years ago, the Aryans of Italy looked up to that bright heaven above, hoc sublime candens, and called it Ju-pitar, Heaven-father.

And a thousand years ago the same Heaven-father and All-father was invoked in the dark forests of Germany by our own peculiar ancestors, the Teutonic Aryans, and his old name of Tiu or Zio was then heard perhaps for the last time.[1]

Muller thought that personification of natural elements turned to deification of these as deities, later on. For instance, He saw that the name Dyaus (Zeus or Jupiter, light-giver, a fitting name for the sky) was later replaced by various gods, who represented some of the principal activities of the sky, such as thunder, rain, storm, evening and morning, night, day, etc.[2] Thus, gradually there originated a pantheon of deities in the Vedas.

James Wheeler classified the more important Vedic deities as follows:

Rain.

Indra, god of the firmament

Varuna, god of the waters

Fire.

Agni, god of fire.

Surya, the sun.

Soma, or Chandra, the Moon.

Air.

Vayu, the god of wind.

Maruts, the breezes who attended upon Indra.

The God or judge of death, Yama

There are also various personifications to whom hymns are address, such as Earth, Sky, Food, Wine, Months, Seasons, Day, Night, and Dawn.[3] However, Surendranath Dasgupta was of the opinion that the gods of the Vedas were impersonal in nature, as their names Agni (Fire), Vayu (Wind), etc also indicated.[4] He classified the gods as terrestrial, atmospheric, and celestial. Subodh Kapoor divides the Vedic gods into three groups: the gods of earth such as Agni and Soma; the gods of the atmosphere such as Indra and the Maruta; and, the gods of heaven such as Mitra and Varuna.[5] There seems to be a three-tier relationship between nature and the divine: earth-atmosphere-heaven.

However, there seems evidence that the various names considered now popularly as deities were not different gods but names of the One. For instance Rig Veda 1.164.46 states:

They call him Indra, Mitra, Varuṇa, Agni, and he is heavenly nobly-winged Garutmān.

To what is One, sages give many a title they call it Agni, Yama, Mātariśvan.[6]

The White Yajur Veda Book 32 also points to the oneness of God in the phrase “is That”. Thus, “Agni is That; the Sun is That; Vâyu and Chandramâs are That. The Bright is That; Brahma is That, those Waters, that Prajâpati. All twinklings of the eyelid sprang from Purusha, resplendent One. No one hath comprehended him above, across, or in the midst. There is no counterpart of him whose glory verily is great.” (WYV 32.1-3).[7] The word pratima translated as “counterpart” by Griffith can also be translated as “image”; thus, the verse seems to speak against the idolization of the deity. He is also called the Bright, Bodiless, Woundless, Sinewless, the Pure which evil hath not pierced, far-sighted, wise, encompassing, and self-existent (WYV 40.8). In the Upanishads, however, the Self itself is declared to be the only true reality. The Self as all is declared as having both form and also being formless (Brihadarayanka Upanishad 2.3.1). The “oneness” verses of the Vedas seem to fit well with the later non-dualistic interpretations of reality and as such could have been precursors of the doctrine, if not later interpolations. Yajur Veda 40 indubitably reflects the beginning of non-dualistic tendencies:

5 It moveth; it is motionless. It is far distant; it is near.

It is within This All; and it surrounds This All externally.

6 The man who in his Self beholds all creatures and all things that be, And in all beings sees his Self, thence doubts no longer, ponders not.

7 When, in the man who clearly knows, Self hath become all things that are, what wilderment, what grief is there in him who sees the One alone?

8 He hath attained unto the Bright, Bodiless, Woundless, Sinewless, the Pure which evil hath not pierced. Far-sighted, wise, encompassing, he self-existent hath prescribed aims, as propriety demands, unto the everlasting Years.

9 Deep into shade of blinding gloom fall Asambhûti's [the Uncreated’s] worshippers. They sink to darkness deeper yet who on Sambhûti [the Created] are intent.

10 One fruit, they say, from Sambhava [Possibility], another from Asambhava [Impossibility]. Thus from the sages have we heard who have declared this lore to us.

11 The man who knows Sambhûti [Creation] and Vinâsa [Annihilation] simultaneously, He, by Vinâsa [Annihilation] passing death, gains by Sambhûti [Creation] endless life.

17 The Real's face is hidden by a vessel formed of golden light. The Spirit yonder in the Sun, the Spirit dwelling there am I. OM! Heaven! Brahma![8]

Obviously, to know Creation and Dissolution at the same time means to transcend the phenomenal world of time, birth, death, and history and be eternal. The Veda aims at eternal life; but finds a possibility only in the inherent immortality of the Self.

Demonology

In Vedic literature, gods and demons seem to be equal in power, though demons became less powerful beings later on. According to Moncure Daniel Conway, demons in Indian literature were previously gods who became demonized later on. He compared this phenomenon with the demonization of deities in Zoroastrianism and suggests a possible political purpose behind the same; possibly, the politics of demonization began in Persia leading to the migration of some of these tribes, whose gods were demonized, into Asia.

The most powerful priesthood carried the day, and they used every ingenuity to degrade the gods of their opponents. Agathodemons were turned into kakodemons. The serpent, worshipped in many lands, might be adopted as the support of sleeping Vishnu in India, might be associated with the rainbow (‘the heavenly serpent’) in Persia, but elsewhere was cursed as the very genius of evil.

The operation of this force in the degradation of deities, is particularly revealed in the Sacred Books of Persia. In that country the great religions of the East would appear to have contended against each other with especial fury, and their struggles were probably instrumental in causing one or more of the early migrations into Western Europe. The great celestial war between Ormuzd and Ahriman—Light and Darkness—corresponded with a violent theological conflict, one result of which is that the word deva, meaning ‘deity’ to Brahmans, means ‘devil’ to Parsees.

The Zoroastrian conversion of deva (deus) into devil does not alone represent the work of this odium theologicum. In the early hymns of India the appellation asuras is given to the gods. Asura means a spirit. But in the process of time asura, like dæmon, came to have a sinister meaning: the gods were called suras, the demons asuras, and these were said to contend together. But in Persia the asuras—demonised in India—retained their divinity, and gave the name ahura to the supreme deity, Ormuzd (Ahura-mazda). On the other hand, as Mr. Muir supposes, Varenya, applied to evil spirits of darkness in the Zendavesta, is cognate with Varuna (Heaven); and the Vedic Indra, king of the gods—the Sun—is named in the Zoroastrian religion as one of the chief councillors of that Prince of Darkness.[9]

| Samudra Manthan or The Churning of the Ocean |

Max Muller considered Asura to be the “oldest name for the living gods” and connected it with the Zend Ahura.[10] Another theory looks at the Asuras as actually the original inhabitants of India that absorbed the Aryan influx and became the authors of the Rig Veda.[11] The theory of looking asuras as the dark-skinned people vanquished by the devas (“the shining ones”) is being discounted by scholars. Wash Edward Hale notes that Hiranyahasta (a term by which the asuras are described in the Rig Veda) "does not mean "dark-skinned." It means "having golden hands" and occurs once in the RV with asura-as an epithet of Savitr, the sun (RV.1.35.10).”[12] Also, according to C.N. Rao, the Asuras were the first gods of India.

There was a perpetual fight...during the course of which some of the Asuras seems to have called truce and agreed to occupy a subordinate and yet important position in the Aryan fold. Varuna, for instance, is an Asura and yet a god of the Aryans. How this came to pass may be accounted for by the fact that originally he was a powerful rival of Indra and passages can be quoted from the Rigveda to show that for some time they were each contending for the upper hand. But in course of time, Varuna contented himself with remaining in the Aryan fold by accepting sovereignty over the 'Antariksha' and administering the Rita or the Law.... Similarly with the Maruts, originally Asuras, but accepting a subordinate yet important position in teh hierarchy of the Aryan gods. It is remarkable that no Suras are mentioned in the Rigveda, but only Asuras and the word Suras is only a late formation on mistaken etymology. That is why also the Asuras are called the Purvadevatah.[13]

Rao’s view seems to accord with the theory that the Asuras went through a process of demonization, and were not yet demonized in the Rig Veda.

It is interesting to also note that Asura is in the beginning seen in connection with Surya (sun) and Savitar in the Rig Veda. In RV.1.35, both Savitar and Asura are called the golden-handed one, and while Savitar is the one who drives away sicknesses and bids the Sun to come and is the one who spreads the bright sky through darksome region, Asura is the one who drives away Rakshasas and Yatudhanas and is referred to as God who is present and is praised by hymns in the evening. Asura is also referred to as the gentle and kind Leader (RV 1.35.7; 1.35.10). In RV.3.29.14, Agni (Fire) is considered to have been brought to life from the Asura’s body. In RV.3.38.4 and 3.38.8, the Sun is referred to as Asura and Savitar. In 3.53.7, Angirases and Virupas are called Asura’s heroes, the Sons of Heaven. In 3.56.8, Asura’s heroes Savitar, Varuna, and Mitra are considered to rule over the three bright realms of the Sky, the Waters, and the Earth. In 4.53.1, Savitar is called the sapient Asura; also, in 5.49.2. In 5.63.3, Varuna and Mitra, the Lords of earth and heaven cause rain on earth by the power (maya) of Asura. In 5.63.4, Mitra-Varuna hide the Sun with cloud and flood of rain and water drops. In 7.6.1, Asura is called the “high imperial Ruler, the Manly One in whom the folk shall triumph… who is as strong as Indra” and is called “the Fort-destroyer.” In” 8.20.17 and 10.67.2, the Creator Dyaus is referred to as “the Asura”. In 8.42.1, Varuna is referred to as the Asura who the heavens, and measured out the broad earth's wide expanses. It is only in 10.138.3, that we first see Arya mentioned along with Asura. In this verse, Indra is said to have overthrown the forts of Pipru who was a conjuring Asura.

Evidence seems to support the theory of Asura-Ahura homogeneity. Also, it has been discovered that one Mitanni treaty does list the names of some of the Vedic gods like Varuna, Mithra, and Nasatya in an order similar to the Vedas. Excerpts from the 14th century B.C. Hatti-Mitanni treaty give the names of the Vedic deities as follows: Mitrassil Arunassil, Indara Nasattiyanna (KBo I 3 Vo 24).[14] The order of the names looks the same as the order of pairs in Rig Veda 10.125.1 “Varuna and Mitra, Indra and Agni, and the Pair of Asvins”, i.e. the Nasatyas. KBo I 1 Vo 55-56 (of the Hatti-Mitanni treaty) has a slight change in the rendering: Mitrassil Uruwanassil, Indar Nasattiyanna leading to a conjecture that Uruwana, or Ruwana meaning “the one in charge of flowing waters,” is Varuna the creator of the water blocking monster Vritta that Indra is praised for killing.[15]

Asura as a divine class continues to feature in the Sama Veda where Indra is referred to as Asura in SV.6.2.12.2. However, in 6.3.5.2, Surya (Sun) is referred to as the slayer of “Dasyus, Asuras, and foes”, hinting possibly to the first demonizing instance of the class. In 9.3.7.3, Indra is referred to as the one who overthrew the great might of the Asura.

In Yajur Veda, we begin to see the casting off of Asura from the solar realm to the territory of the night. In 1.3.14 Agni is referred to as Rudra, the Asura of the mighty sky. However, by 1.5.1, we begin to see the first conflict between the gods and the Asuras in which the gods win. Agni (previously mentioned as an Asura) is seen as the one who runs away with the wealth that the gods deposited in him. In 1.5.9 we first find the statement that the day belongs to the gods and the night belongs to the Asuras, who entered night with the treasures of the gods. The gods, perceiving that “the night is Agni’s” begin praising Agni thinking he will restore to them their cattle, and Agni does deliver them their cattle from “night to day”. In 1.6.11 it is seen that the gods deceived the Asuras with the help of Agni. In 2.2.6, Agni has become associated with the gods, and the place of the gods is the Agni Vaishvarana, the year. From that place the gods drove away the Asuras. In 2.3.7, the gods are seen as defeated by the Asuras and as, having lost power and strength, made servants. However, Indra tries to pursue but cannot win and so he turns to Prajapati’s stipulated sacrifice by which he receives power and strength. Therefore, it is said that through the sacrifice and Agni, the gods defeated the Asuras. In 2.4.1, we find the first classification of sides. gods, men, and the Pitrs (fathers) on one side; Asuras, Rakshashas (giants), and Pishachas (cannibals) on the other. Thus, appears the first classification of the demonic triad in Vedic history.

In the White Yajur Veda 40.3, the Asuras are considered to inhabit the worlds that are enwrapt with blinding gloom. To them, when life on earth is done, depart the men who kill the Self.

Anthropology

Humans are referred to as mortals in the Vedas (SV.1.5.2). Men are Manu’s race (SV.2.2.8). Manu appointed Agni as the chief priest (RV.1.13.1; 1.14.11; SV.5.1.10). Agni, kindled by mortals is the immortal fire that mediates between the immortal gods and mortal men. Humans are divided into two groups: the law-abiders versus the Dasyus (or Dasas), the riteless, lawless ones (SV.3.1.3.2; 6.2.20.3). The Dasyus are said to be on the side with Asuras and foes (SV.6.3.5.2). After death, the soul departs to a place prepared by Yama, the god of death (RV.10.14.2). There is no talk of reincarnation yet during the Vedic period. Also, Yama is not the god of hell, but the god of the place where the fathers have gone.

Soteriology

The invocations in the Vedas usually call for blessings of rain, cattle, fruitfulness, and for defeat of the evil foes. In RV.1.24.14, we find a prayer to Varuna the Asura to lose the devotee of the bonds of sins. In RV.1.34.11, the Ashvins are invoked at the time of sacrifice to “make long our days of life, and wipe out all our sins: ward off our enemies; be with us evermore.” In 1.129.5, though used as a comparative for Indra, the concept of the Priest as one who drives all the sins of man away is found. In 2.28.9 and 5.85.8, Varuna is seen as the one who drives away all sins. In 7.86.5, there are two kinds of sins from which the devotee prays for deliverance: sins committed by the fathers and sins committed by self. In 10.105.8, the prayer is that Indra would grind off all sins and the observance is that he is not pleased with prayerless sacrifices.

Integral to the Vedic religion is the concept of Sacrifice (for which the Vedic hymns were mainly composed). Sacrifice is the means of obtaining blessings, protection, and ascendance to the realm of the gods. Food was offered to the gods through the sacrificial rite, and the sacrifice destroyed the evil spirits and rakshashas.

Some humans attained the life of spirits (RV.10.15.1). RV.10.15.14 talks of those who were consumed by fire and those not cremated, both of whom are invoked to be granted the world of spirits and their own body; suggesting that both cremation and burial were accepted in the Vedas. Shukla Yajur Veda 30.5 mentions hell as the place where murderers go. Atharva Veda 12.4.36 states that hell is reserved for anyone who doesn’t give a Cow to Brahmans when they ask for it.

[1] Max Muller, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religions of India (London: Longmans, 1901), p.223

[2] Ibid, p.218

[3] Wheeler, The History of India…, pp.9,10

[4] Surendranath Dasgupta, History of Indian Philosophy, Vol.1(Cambridge, 1922) , p.16 at Gutenberg.net

[5] Subodh Kapoor (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of Vedic Philosophy, Vol. 8 (Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 2002), p.2280

[6] Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

[7] The Texts of the White Yajurveda, tr. Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1899], at sacred-texts.com

[8] The Texts of the White Yajurveda, tr. Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1899], at sacred-texts.com. Parenthetical suggestions, mine.

[9] Moncure Daniel Conway, Demonology and Devil-lore (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1879), pp.25,26 [Gutenberg.org]

[10] Max Muller, Lectures…, p.197

[11] Malati Shendge, “Obstacles to Identifying the Origins of India's History and Culture”.

[12] Wash Edward Hale, Asura in Early Vedic Religion (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1986), p.19

[13] Chilukuri Narayana Rao, An Introduction to Dravidian Philology (Asian Educational Services, 1929), pp.37,38. Purvadevatah means “previous or older gods”

[14] Arnaud Fournet, “About the Mittanni-Aryan Gods”, Journal of the Indo-European Studies, Vol.38, No.1&2., 2010. Academia.edu

[15] Ibid

The Vedas

|

| Rig Veda Manuscript |

The four main divisions of the Vedas are as follows:

Samhitas: These were collections of metrical hymns, prayers, and songs usually sung or chanted during the performance of various rites and sacrifices.

Brahmanas: These were prose commentaries and theological discussions on the meaning of the various texts, sacrifices, and ceremonies.

Aranyakas: Also known as the “forest texts”, these were, partly appended to the Aranyakas and partly independent, commentaries and meditations by hermits living in the forest on the significance of the rituals and sacrifices described in the Vedic hymns.

Upanisads: These were also usually either part of the Aranyakas or independent of them, without any absolute dividing point. For instance, The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is both an Aranyaka and an Upanishad and forms the last part of the Satapatha-Brahmana, a Brahmana of the White Yajur-Veda.[2] The Upanishads are mystical contemplations on the meaning of the world, soul, life, death, and reality.

Rig Veda: The word Rig comes from ṛc and means “praise, verse”. Thus, Rig Veda is the book of Praise-knowledge. The Veda is organized into 10 books, known as Mandalas, each consisting of several hymns or Suktas. The Suktas consist of stanzas called ṛc that can be further analysed into pada (foot) or verses.

Sama Veda: The collection is derived from the word Saman, meaning "melodies"; thereby, Sama Veda is the book of the "knowledge of melodies". It is considered that the hymns in this book were mainly used during the Soma sacrifice and many of the hymns are repeated from the Rig Veda.

Yajur Veda: Yajus means “sacrificial formula”; thus, Yajur Veda gives the “knowledge of sacrificial formulas”. There are two primary versions of this, viz. the Shukla Yajur Veda (White Yajur Veda) and the Krishna Yajur Veda (Black Yajur Veda). While the White Yajur Veda focuses on liturgy, the Black Yajur Veda has more explanatory material about the rituals.[3]

Atharva Veda is the book of the “knowledge of magic formulas” (atharvan). It is a collection of spells, prayers, charms, and hymns with “prayers to protect crops from lightning and drought, charms against venomous serpents, love spells, healing spells,” containing hundreds of verses, some derived from the Rig Veda.[4]

RIG VEDA:

Brahmanas: Aitereya and Kaushitaki or Sankhayana

Aranyakas: Aitereya and Kaushitaki or Sankhayana

Upanishads: Aitereya (part of Aitereya Samhita) and Kaushitaki (part of Kaushitaki or Sankhayana Aranyaka)

SAMA VEDA:

Brahmanas: Chandogya, Tandya and Jaiminiya or Talavakara

Aranyaka: Jaiminiya or Talavakara and Chandogya

Upanishads: Chandogya (part of Chandogya Brahmana) and Kena (part of Jaiminiya and Talavakara Brahmana)

YAJUR VEDA:

Shukla Yajur Veda:

Brahmanas: Satapatha

Aranyaka: Brihadaranyaka

Upanishads: Isha (part of Vajasaneya Samhita) and Brihadaranyaka (part of Satapatha Brahmana)

Krishna Yajur Veda:

Brahmana and Aranyaka are considered together in Taittiriya Samhita and contains Maitrayani Brahmana

Upanishad: Katha and Svetasvatara

ATHARVA VEDA:

Brahmanas: Gopatha

Aranyaka: None known

Upanishads: Prasna, Mundaka and Mandukya

[1] The Rig Veda, http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/RV/ Accessed on April 24, 2015.

[2] Dominic Goodall, R.C. Zaehner (eds), Hindu Scriptures (University of California Press, 1996), xi

[3] The Texts of the White Yajurveda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith [1899], at sacred-texts.com

[4] Hymns of the Atharva Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1895], at sacred-texts.com

[5] Ashim Kumar Bhattacharya, Hindu Dharma: Introduction to Scriptures and Theology (London: iUniverse, 2006), pp.6,7

Vedic Society (C.1750-600 BC)

The Vedic Age begins with the supposed arrival of the Aryans and the composition of the Rig Veda. Again, there are differences of opinion regarding whether the Aryans really arrived or they were the original inhabitants of the land. For instance, in his History of India, Mountstuart Elphistone wrote, “There is no reason whatever for thinking that the Hindus ever inhabited any country but their present one; and as little for denying that they may have done so before the earliest trace of their records or traditions.”[1] Elphinstone argued this from the absence of any Vedic allusion “to a prior residence, or to a knowledge of more than the name of any country out of India.” However, his arguments do not convince most historians. Keay notes:

Caste System

Scholarly consensus agrees on the point that the Aryan religion as practiced in the Rig Veda was simpler and devoid of the caste-system. In his History of India (1867), James Talboys Wheeler separated the Vedic age from the Brahminic age (also now called the Age of the Epics or the Puranic Age) and points out the following chief differences between the two:

There are some scholars who maintain that the Varna system did not exist in the age of the Rig Veda. This statement is based on the view that the Purusha Sukta is an interpolation which has taken place long after the Rig Veda was closed. Even accepting that the Purusha Sukta is a later interpolation, it is not possible to accept the statement that the Varna system did not exist in the time of the Rig Veda. Such a system is in open conflict with the text of the Rig Veda. For, the Rig Veda, apart from the Purusha Sukta, does mention Brahmina, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas not once but many times. The Brahmins are mentioned as a separate Varna fifteen times, Kshatriyas nine times. What is important is that the Rig Veda does not mention Shudra as a separate Varna. If Shudras were a separate Varna there is no reason why the Rig Veda should not have mentioned them. The true conclusion to be drawn from the Rig Veda is not that the Varna system did not exist, but that there were only three Varnas and that Shudras were not regarded as a fourth and a separate Varna.[6]

Ambedkar theorized that the Shudras originally belonged to the Kshatriya class and quotes Shanti Parva of Mahabharata 60.38-40 as a primary piece of evidence, where it says: “It has been heard by us that in days of old a Sudra of the name of Paijavana gave a Dakshina (in one of his sacrifices) consisting of a hundred thousand Purnapatras, according to the ordinance called Aindragni.” This mentioning of Paijavana in the text, however, was in order to give evidence from history of a Shudra who observed this rule that offering of sacrifices was mandatory for Shudras as well as it is for the upper castes. According to this rule, since the Shudra is not allowed to utter the mantras, he was to offer sacrifices called the Purnapatras without observing the vows laid down by the Vedas.[7] However, the very fact that these rules come later on and are requiring a citation of an example from the past seems to indicate that the Varna system as it came to be stipulated in this section of the Mahabharata was not prevalent during the Vedic age. In fact, according to K. M. Ganguli, translator of the Mahabharata in English (thus far the only complete translation):

The Santi Parva is a huge interpolation in the Mahabharata, in the genre known as 'wisdom literature.' The narrative progression is placed on hold almost from the first page. Instead we get a long and winding recapitulation of Brahmanic lore, including weighty treatises on topics such as kingcraft, metaphysics, cosmology, geography, and mythology. There are discussions of the Sankya and Yoga philosophical schools, and mentions of Buddhism. It is apparent that the Santi Parva was added to the Mahabharata at a later time than the main body of the epic.[8]

Widow Remarriage

Rig Veda 10.18 and Atharva Veda 18.3 have references to the widow during the time of funeral. There have been interpretations that saw these hymns as ratifying the custom of Sati (in which a widow was cremated alive with her dead husband). However, the interpretations are controversial owing to the obscurity of the text. Some have looked at these verses as a call to the widow to rise up from mourning and return to the world of life or resume her place in the world where battles are still to be fought.[9] In fact, it is suggested that it is the brother of the widow’s husband who raises his sister-in-law up with the words, “Rise up, woman, into the world of the living.”[10] The brothers and relatives seem to be pleading the widow to release her husband’s body for cremation. It is also suggested that the hymn also pronounces on the widow a blessing at her second marriage with the words in RV.10.18.9: “Go up O woman to the world of living; You stand by this one who is deceased; Come! to him who grasps your hand, Your second spouse (didhisu), You have now entered into the relationship Of wife and husband.”[11] The controversial nature of this passage will be evident from comparing it to Griffith’s translation of the same as “From his dead hand I take the bow be carried, that it may be our power and might and glory. There art thou, there; and here with noble heroes may we o’ercome all hosts that fight against us.”[12] Nevertheless, there is modern consensus on the interpretation that the Vedic texts only describe a form of mimetic death of the widow with her husband. She was wedded to him for life; but, on his death, she became dead to him and he to her, whereby she was expected to return to the world of the living, where she was free from her former husband, now to remarry another. This interpretation seems more in keeping with the ancient law-systems of the then world. For instance, the Code of Hammurabi (ca.2250 B.C.), states:

NOTES

[1] Mountstuart Elphinstone, The History of India: The Hindu and Mohametan Periods, 5th edn. (London: John Murray, 1866), p.54

[2] John Keay, India: A History, p.27

[3] Ibid, p.27

[4] James Talboys Wheeler, The History of India from the Earliest Ages, Vol I: The Vedic Period and the Mahabharata (London: N. Trubner & Co, 1867), p.6

[5] Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

[6] B. R. Ambedkar, Who Were the Shudras? Vol.I (Thackers, 1970)

[7] Kisari Mohan Ganguli (tr), The Mahabharata (1883-1896), sacred-texts.com, pp.131-132

[8] Ibid. pp.131-132

[9] Carl Olson, The Many Colors of Hinduism (Rutgers University Press,2007), p.265

[10] Elena Efimovna Kuzʹmina, The Origin of the Indo-Iranians (Leiden: BRILL, 2007), p.188

[11] Arun R. Kumbhare, Women in India: Their Status Since the Vedic Times (Bloomington: iUniverse, 2009), pp.14,15

[12] Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

[13] Hammurabi’s Laws, tr. by M. E. J. Richardson (London: T&T Clark, 2000), p.99

..it is certainly curious that the Vedas say nothing of life in central Asia, nor of an epic journey thence through the mountains… The usual explanation is that, by the time the Vedas were composed, this migration was so remote that all memory of it had faded…[2]Allowing “first for a major time-lapse (say two hundred years) between the Late Harappan phase and the Aryan arrival in India, and then for a plausible memory gap (say another two hundred years) between arrival and the composition of the earliest Vedas,”[3] Keay suggests the period between 1500 BC and 1300 BC as the time of the Aryan arrival. He is among the group of scholars that favor a more gradual migration theory to the previous Aryan-invasions theory. He thinks the multiple waves of migration theory best fits the fact of the Aryanisation of the entire sub-continent. However, as we have seen earlier, there are other theories to account for the fact of Aryanisation (or Sanskritisation). For instance, there is the Brahminic mission theory as well as the Asura composition of the Rig Veda theory. But, whatever, we are only left more with theories and not established facts with regard to the origin issues. Nevertheless, we have at least one advantage: the Rig Veda, considered to be the only existent earliest record of people in the Indian sub-continent.

Caste System

Scholarly consensus agrees on the point that the Aryan religion as practiced in the Rig Veda was simpler and devoid of the caste-system. In his History of India (1867), James Talboys Wheeler separated the Vedic age from the Brahminic age (also now called the Age of the Epics or the Puranic Age) and points out the following chief differences between the two:

In the Vedic period the Brahmins were scarcely known as a separate community; the caste system had not been introduced, and gods were worshipped who were subsequently superseded by deities of other names and other forms. In the Brahminic period the Brahmins had formed themselves into an exclusive ecclesiastical hierarchy, endowed with vast spiritual powers, to which even the haughtiest Rajas were compelled to bow. The caste system had been introduced in all its fulness, whilst the old Vedic gods were fast passing away from the memory of man, and giving place to the three leading Brahminical deities–Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva. Again, the Vedic period is characterized by a patriarchal simplicity, which is wanting in the Brahminic age, when the luxury and splendour of the Hindu Rajas had reached a climax side by side with the increased power and influence exercised by the Brahminical hierarchy.[4]However, the 90th hymn “Purusha” of the 10th Book in the Rig Veda does mention castes in the following words:

When they divided Puruṣa how many portions did they make?But, many scholars consider the above text to have been interpolated by later protagonists of the Varna (caste) system. However, Dalit leader and architect of the Indian Constitution, B.R. Ambedkar, thought it untrue to a study of the Vedas to consider that the caste-system was absent from the Vedic age. However, he did try to point out that the fourth caste, Shudra (considered to be the lowest) was not original to the Vedic age, though texts such as the Purusha Sukta quoted above could have been tampered with by Brahmin priests of the latter period.

What do they call his mouth, his arms? What do they call his thighs and feet?

The Brahmin was his mouth, of both his arms was the Rājanya made.

His thighs became the Vaiśya, from his feet the Śūdra was produced.[5]

There are some scholars who maintain that the Varna system did not exist in the age of the Rig Veda. This statement is based on the view that the Purusha Sukta is an interpolation which has taken place long after the Rig Veda was closed. Even accepting that the Purusha Sukta is a later interpolation, it is not possible to accept the statement that the Varna system did not exist in the time of the Rig Veda. Such a system is in open conflict with the text of the Rig Veda. For, the Rig Veda, apart from the Purusha Sukta, does mention Brahmina, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas not once but many times. The Brahmins are mentioned as a separate Varna fifteen times, Kshatriyas nine times. What is important is that the Rig Veda does not mention Shudra as a separate Varna. If Shudras were a separate Varna there is no reason why the Rig Veda should not have mentioned them. The true conclusion to be drawn from the Rig Veda is not that the Varna system did not exist, but that there were only three Varnas and that Shudras were not regarded as a fourth and a separate Varna.[6]

|

| Ambedkar believed that the caste- supportive texts of Vedas were later interpolations |

The Santi Parva is a huge interpolation in the Mahabharata, in the genre known as 'wisdom literature.' The narrative progression is placed on hold almost from the first page. Instead we get a long and winding recapitulation of Brahmanic lore, including weighty treatises on topics such as kingcraft, metaphysics, cosmology, geography, and mythology. There are discussions of the Sankya and Yoga philosophical schools, and mentions of Buddhism. It is apparent that the Santi Parva was added to the Mahabharata at a later time than the main body of the epic.[8]

Widow Remarriage

Rig Veda 10.18 and Atharva Veda 18.3 have references to the widow during the time of funeral. There have been interpretations that saw these hymns as ratifying the custom of Sati (in which a widow was cremated alive with her dead husband). However, the interpretations are controversial owing to the obscurity of the text. Some have looked at these verses as a call to the widow to rise up from mourning and return to the world of life or resume her place in the world where battles are still to be fought.[9] In fact, it is suggested that it is the brother of the widow’s husband who raises his sister-in-law up with the words, “Rise up, woman, into the world of the living.”[10] The brothers and relatives seem to be pleading the widow to release her husband’s body for cremation. It is also suggested that the hymn also pronounces on the widow a blessing at her second marriage with the words in RV.10.18.9: “Go up O woman to the world of living; You stand by this one who is deceased; Come! to him who grasps your hand, Your second spouse (didhisu), You have now entered into the relationship Of wife and husband.”[11] The controversial nature of this passage will be evident from comparing it to Griffith’s translation of the same as “From his dead hand I take the bow be carried, that it may be our power and might and glory. There art thou, there; and here with noble heroes may we o’ercome all hosts that fight against us.”[12] Nevertheless, there is modern consensus on the interpretation that the Vedic texts only describe a form of mimetic death of the widow with her husband. She was wedded to him for life; but, on his death, she became dead to him and he to her, whereby she was expected to return to the world of the living, where she was free from her former husband, now to remarry another. This interpretation seems more in keeping with the ancient law-systems of the then world. For instance, the Code of Hammurabi (ca.2250 B.C.), states:

If a widow with small children has come to a decision to enter the house of a second man, she shall not enter without legal authority.

Before she enters the house of another man the judges will make decisions about the affairs in her first husband's house and entrust her first husband's household to that woman and her second husband, and they shall make them deposit a written statement.

They shall take care of the house and bring up the children.

They shall not sell the furniture for silver.

Anyone who buys the belongings of a widow's sons shall forfeit his silver.

The property shall return to its owner. (L177)[13]

For the woman who has a husband is bound by the law to [her] husband as long as he lives. But if the husband dies, she is released from the law of [her] husband. So then if, while [her] husband lives, she marries another man, she will be called an adulteress; but if her husband dies, she is free from that law, so that she is no adulteress, though she has married another man. (Romans 7:2-3, The Bible, NKJV).

NOTES

[1] Mountstuart Elphinstone, The History of India: The Hindu and Mohametan Periods, 5th edn. (London: John Murray, 1866), p.54

[2] John Keay, India: A History, p.27

[3] Ibid, p.27

[4] James Talboys Wheeler, The History of India from the Earliest Ages, Vol I: The Vedic Period and the Mahabharata (London: N. Trubner & Co, 1867), p.6

[5] Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

[6] B. R. Ambedkar, Who Were the Shudras? Vol.I (Thackers, 1970)

[7] Kisari Mohan Ganguli (tr), The Mahabharata (1883-1896), sacred-texts.com, pp.131-132

[8] Ibid. pp.131-132

[9] Carl Olson, The Many Colors of Hinduism (Rutgers University Press,2007), p.265

[10] Elena Efimovna Kuzʹmina, The Origin of the Indo-Iranians (Leiden: BRILL, 2007), p.188

[11] Arun R. Kumbhare, Women in India: Their Status Since the Vedic Times (Bloomington: iUniverse, 2009), pp.14,15

[12] Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

[13] Hammurabi’s Laws, tr. by M. E. J. Richardson (London: T&T Clark, 2000), p.99

Religion in the Pre-Vedic Age (c3000-1700 BC)

The earliest traces of some form of religion in the Indian sub-continent were discovered at the excavated sites of the Harappan Civilization (also known as the Indus-Valley Civilization) that is dated to have flourished between c3000-1700BC.

Modern scholarship seems to be more in favor of the theory that the Harappan Civilization was closer to Dravidian than to Aryan. This is concluded on the basis of meticulous study especially of the Indus script on seals and on figures discovered at the sites.

Asko Parpola of Helsinki University, who specializes in the Indus script, has tried to argue a relationship between the Indus and Tamil languages.[1] In his lecture, “A Dravidian Solution to the Indus Script Problem,” delivered at the World Classical Tamil Conference, Coimbatore, in June 2010, Parpola suggested that the underlying language of the Indus script was Proto-Dravidian and tried to identify in it astrological symbols and also religious deities that were supposedly borrowed later by the Aryans. Eminent among these deities were the Aryan/Dravidian fertility god Rudra/Shiva and the Tamil god of war Murukan who, Parpola suggests, were descended from a Proto-Dravidian deity mentioned in the Indus inscriptions. He begins by identifying the fish sign in the seals (see Fig.1) as indicating the name of a deity. Parpola suggests that the Indus inscriptions can be understood in context of the “fertility cult connected with fig trees, a central Hindu myth associated with astronomy and time-reckoning, and chief deities of Hindu and Old Tamil religion.”[2]

In 2006 and 2008, at Sembiyankandiyur of Tamilnadu, a celt and pottery having inscriptions resembling the Indus script were excavated strengthening the proto-Dravidian hypothesis.[3] In November 2014, the Indian scholar on Indus script, Iravatham Mahadevan, presented evidences to show that the Indus language was actually an early form of the Dravidian. He concluded that ‘’the Earliest Old Tamil, which has retained the Dravidian roots of the Indus phrase still, is firmly interlinked, but with modified meanings.”[4] In the paper titled “Dravidian Proof of the Indus Script via the Rig Veda: A Case Study”, he concluded:

Much about the religion of the significant Harappan civilization seems to still be obscure, mainly owing to disagreements and lack of consensus regarding attempts to decipher the Indus inscriptions. However, it has been generally opined that the possible features of the Harappan religion may have been:

It still needs to be known what happened to the Harappan civilization and why it is not mentioned in any of the Vedic writings; also, the nature of the relation between the Harappan, Indo-Aryan, and the Dravidian civilizations, if any, still need to be discovered. To some extent, however, at least the following have been established as the discontinuities between the Harappan and Vedic cultures:

However, if the fertility cult was really prevalent among the Harappans as most historians think it was, the following facts about their beliefs can be generalized through a psychological and theological analysis (on the basis of archaeological findings):

NOTES

[1] Asko Parpola, “Indus Script: Penetrating Into Long-Forgotten Picto+Graphic Messages," http://www.harappa.com/script/parpola6.html. Accessed on April 13, 2015

[2] Asko Parpola, “A Dravidian Solution to the Indus Script Problem,” delivered at the World Classical Tamil Conference, Coimbatore, in June 25, 2010 (Chennai: Central Institute of Classical Tamil).

[3] “Discovery of a Century” in Tamilnadu, The Hindu, May 1, 2006. “From Indus Valley to Coastal Tamilnadu”, The Hindu, May 3, 2008. Thehindu.com

[4] “Indus Script Early Form of Dravidian”, The Hindu, November 15, 2014.

[5] Iravatham Mahadevan, “Dravidian Proof of the Indus Scrip

via the Rig Veda: A Case Study”, Bulletin of the Indus Research Center, No.4, Nov 2014 (Chennai: Indus Research Center), p.37

[6] “Interpreting the Indus Script: The Dravidian Solution”, http://203.124.120.60/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/Kuppamadd.pdf

[7] “Dravidian Proof…”, p.40

[8] Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient and Medieval India (New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley, 2009) pp.171-172

[9] Ibid, p.171

[10] Edwin Oliver James, The Tree of Life (Netherlands: E.J.Brill, 1966), p.23

[11] Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient… p.171

[12] Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan: An Archaeological History, Vol. IV. (Foursome Group, 2014), pp.236-243

[13] Iravatham Mahadevan, “Interpreting the Indus Script…” Also see R.S. Sharma, Looking for the Aryan (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1995), p.17

[14] http://www.harappa.com/script/mahadevantext.html

[15] Romila Thapar, The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (New Delhi: Penguin, 2002), p.110

[16] Ibid, p.110

[17] Ibid, p.110

[18] Ibid, p.110

[19] Ibid,p.110

[20] Ibid,p.110

[21] “Burial of Adult Man, Harappa”, http://www.harappa.com/indus/71.html Accessed on April 14, 2015

[22] C.L.Fabri, “The Punch-marked Coins: A Survival of the Indus Civilisation”, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 2 (Apr., 1935), pp. 307-318 (Cambridge University Press)

[23] Jane Mcintosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives (California: ABC-CLIO, 2008), pp.183-184

[24] Genesis 12

[25] Malati J. Shendge, The Language of the Harappans: From Akkadian to Sanskrit (New Delhi: SMA Publications, 1997), p.96

[26] Malati Shendge, “Obstacles to Identifying the Origins of India's History and Culture,” p.11. http://jies.org/Shenge.pdf

[27] See Stephen Murmu, “Understanding the Concept of God in Santal Traditional Myths,” Indian Journal of Theology, Vol.38 No.1.(Serampore Theological Department, 1996). Also Don Richardson, Eternity in their Hearts (USA: Regal Books, 1981, 2005), pp.47-50.

Modern scholarship seems to be more in favor of the theory that the Harappan Civilization was closer to Dravidian than to Aryan. This is concluded on the basis of meticulous study especially of the Indus script on seals and on figures discovered at the sites.

|

| Fig.1 Unicorn Seal |

In 2006 and 2008, at Sembiyankandiyur of Tamilnadu, a celt and pottery having inscriptions resembling the Indus script were excavated strengthening the proto-Dravidian hypothesis.[3] In November 2014, the Indian scholar on Indus script, Iravatham Mahadevan, presented evidences to show that the Indus language was actually an early form of the Dravidian. He concluded that ‘’the Earliest Old Tamil, which has retained the Dravidian roots of the Indus phrase still, is firmly interlinked, but with modified meanings.”[4] In the paper titled “Dravidian Proof of the Indus Script via the Rig Veda: A Case Study”, he concluded:

- The language of the Indus Civilisation was an early form of Dravidian.

- Due to the migration of a section of the Indus population southwards, forming some settlements in South India, the Indus Dravidian influenced the South Dravidian languages. The earliest attestations of such influence are found in Old Tamil.

- The Vedic Age succeeded the Indus Civilisation. The RV [Rig Veda] itself is a product of the composite culture. The time interval between the Indus texts and the RV must have been sufficiently long to account for the dim recollections and mythologisation seen in the Vedic equivalents of the Indus names and titles. [5]

Much about the religion of the significant Harappan civilization seems to still be obscure, mainly owing to disagreements and lack of consensus regarding attempts to decipher the Indus inscriptions. However, it has been generally opined that the possible features of the Harappan religion may have been:

- Fertility cult (as evident through figures with explicit and exaggerated sexual organs)[8]

- Mother-goddess cult[9]

- Worship of trees[10]

- Offerings to deities[11]

- Pre-eminence of the fish and fig symbols

- Astrology and astro-deities

It still needs to be known what happened to the Harappan civilization and why it is not mentioned in any of the Vedic writings; also, the nature of the relation between the Harappan, Indo-Aryan, and the Dravidian civilizations, if any, still need to be discovered. To some extent, however, at least the following have been established as the discontinuities between the Harappan and Vedic cultures:

- The absence from Harappan of horse and the chariot with spoke wheels which were the defining features of Indo-Aryan societies.[13]

- The absence from Vedic literature of any reference to the Harappan civilization (to its great cities).[14]

- The absence from Rig Veda of the essential characteristics of Harappan urbanization like "cities with a grid pattern in their town plan, extensive mud-brick platforms as a base for large structures, monumental buildings, complex fortifications, elaborate drainage systems, the use of mud bricks and fired bricks in buildings, granaries or warehouses....”.[15]

- The absence from Rig Veda of the elaborate system of commerce used in the Harappan. “There are no references to different facets or items of an exchange system, such as centres of craft production, complex and graded weights and measures, forms of packaging and transportation, or priorities associated with categories of exchange.”[16]

- The absence from Rig Veda “of a sense of the civic life founded on the functioning of planned and fortified cities. It does not refer to non-kin labour, or even slave labour, or to such labour being organized for building urban structures.”[17]

- Religious discontinuities: “Terracotta figurines are alien and the fertility cult meets with strong disapproval. Fire altars… are of a shape and size not easily identifiable at Harappan sites as altars. There is no familiarity from mythology with the notion of an animal such as the unicorn, mythical as it was, nor even its supposed approximation in the rhinoceros, the most frequently depicted animal on the Harappan seals. The animal central to the Rig-Veda, the horse, is absent on Harappan seals.”[18]

- No mention of script or seals in the Rig Veda.[19]

- Sculptured representation of the human body seems unknown in the Rig Veda.[20]

However, if the fertility cult was really prevalent among the Harappans as most historians think it was, the following facts about their beliefs can be generalized through a psychological and theological analysis (on the basis of archaeological findings):

|

| Priest-King, Mohenjadaro |

- Naturalistic Spirituality. The Harappans seemed to believe in divine immanence to a naturalistic extent. This meant that they didn’t have the concept of a transcendent God as Creator of the world. The worshipping of sex organs or exaggerating sexual symbolism in ritual became the way of stimulating fertility, either through the appeasement of some fertility deity or through tapping into assumed fertility powers of nature. Creative power became immanent and naturalistic. If a fertility deity was involved, some form of appeasement through offerings and sacrifices might have also existed. In essence, the divine and the natural are so fused together that the divine assumes the natural in aggrandized forms.

- Polytheism. The findings seem to indicate a number of gods and goddesses that the Harappan may have veneered.

Idolatry. Obviously, the Harappan religion was idolatrous, indicating either a belief in the idol itself or in the spirit/power represented by the idol. - Priestcraft. An elaborate religious system of a polytheistic, naturalistic nature makes it possible that there were architects and mediators of religion; either rulers who were considered to be divine or priest-kings, or just priests. In fact, there is a sculpture unearthed at Mohenjadaro (see Fig.2) that is considered to be of a priest-king.

- Burial. Skeletons of buried humans give evidence that the Harappans practiced burial customs. The body would be decked with ornaments, possibly wrapped in a shroud, and placed in a wooden coffin along with offerings in pots.[21]

The Aryas were a foreign refugee group which trekked to the Indus valley already inhabited by the Asuras and others. They clashed and the political power of the Asuras received a serious jolt (1850 B.C.) but they continued to rule even upto 1300 B.C. The Aryas became acculturated in the Asura culture and language. The Asura language Sumero-Akkadian changed to the language of Rgveda by about 1500 B.C. The Rgveda, other Vedas and Vedic literature as well as the Indus civilization are the creations of the Asuras and their allies and as much represent the indigenous genius and effort. The Indus civilization is the matrix of Indian culture, and India's history begins with the Indus civilization, the Rgveda representing its literary creativity.If Malati’s hypothesis is true, we may find a key to understand the religion of the Harappans in the religion of Sumerians, especially since they seem to have continued to have commerce with each other. Harappan religion was as polytheistic, idolatrous, and nature-related as was the Sumerian and Chaldean. In addition, both the Dravidians and the Aryans have their origin in Sumer, or the plains of Shinar from where they were dispersed. That might also explain the similarities in the signs found in the Indus seals and inscriptions found elsewhere (from Sumer to the South-East Asia). In addition, it might also explain the similarities in the Flood story of Manu, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Biblical story of the Flood. Perhaps, one might also find the roots of the caste-system in the master-slave class system, that seems apparent from an analysis of dwelling units and terracotta (of elaborately dressed mistresses versus scantily dressed slaves) found in the Indus Valley. The priest-kings of Harappa could have become the Brahmins of the Vedas later on. But, at this juncture where there is a lack of conclusively deciphered documentary evidence from the Harappan sites, historical interpretation only abounds in inductive hypothetical generalizations. As far as the origin of tribes such as the Santhals is concerned, anthropologists have found evidences in their folklore of their relationship with the world of the Bible. They have found striking similarities between the Biblical account and the story of creation and the global flood among the Santhals, which points at the Mesopotamian region as their place of origin.[27]

…Thus Sanskrit, as per this view point, has descended from Sumero-Akkadian, a mixed language. It follows logically from this that the ancestors of Greeks and the Romans may have been in touch with the Sumero-Akkadian speaking population to which the similarities between these languages should be traced. And instead of a hypothetical construct like the proto-Indo-European, a real language like Akkadian mixed with Sumerian may be considered a parent. This should possibly help to dissolve the many intriguing difficulties. It is worth a trial. If found unworkable, it can be abandoned at any stage which will fix the limit of this postulate. However, in a scientific pursuit, it is necessary to try new alternatives.[26]

NOTES

[1] Asko Parpola, “Indus Script: Penetrating Into Long-Forgotten Picto+Graphic Messages," http://www.harappa.com/script/parpola6.html. Accessed on April 13, 2015

[2] Asko Parpola, “A Dravidian Solution to the Indus Script Problem,” delivered at the World Classical Tamil Conference, Coimbatore, in June 25, 2010 (Chennai: Central Institute of Classical Tamil).

[3] “Discovery of a Century” in Tamilnadu, The Hindu, May 1, 2006. “From Indus Valley to Coastal Tamilnadu”, The Hindu, May 3, 2008. Thehindu.com

[4] “Indus Script Early Form of Dravidian”, The Hindu, November 15, 2014.

[5] Iravatham Mahadevan, “Dravidian Proof of the Indus Scrip

via the Rig Veda: A Case Study”, Bulletin of the Indus Research Center, No.4, Nov 2014 (Chennai: Indus Research Center), p.37

[6] “Interpreting the Indus Script: The Dravidian Solution”, http://203.124.120.60/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/Kuppamadd.pdf

[7] “Dravidian Proof…”, p.40

[8] Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient and Medieval India (New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley, 2009) pp.171-172

[9] Ibid, p.171

[10] Edwin Oliver James, The Tree of Life (Netherlands: E.J.Brill, 1966), p.23

[11] Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient… p.171

[12] Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan: An Archaeological History, Vol. IV. (Foursome Group, 2014), pp.236-243

[13] Iravatham Mahadevan, “Interpreting the Indus Script…” Also see R.S. Sharma, Looking for the Aryan (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1995), p.17

[14] http://www.harappa.com/script/mahadevantext.html

[15] Romila Thapar, The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (New Delhi: Penguin, 2002), p.110

[16] Ibid, p.110

[17] Ibid, p.110

[18] Ibid, p.110

[19] Ibid,p.110

[20] Ibid,p.110

[21] “Burial of Adult Man, Harappa”, http://www.harappa.com/indus/71.html Accessed on April 14, 2015

[22] C.L.Fabri, “The Punch-marked Coins: A Survival of the Indus Civilisation”, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 2 (Apr., 1935), pp. 307-318 (Cambridge University Press)

[23] Jane Mcintosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives (California: ABC-CLIO, 2008), pp.183-184

[24] Genesis 12

[25] Malati J. Shendge, The Language of the Harappans: From Akkadian to Sanskrit (New Delhi: SMA Publications, 1997), p.96

[26] Malati Shendge, “Obstacles to Identifying the Origins of India's History and Culture,” p.11. http://jies.org/Shenge.pdf

[27] See Stephen Murmu, “Understanding the Concept of God in Santal Traditional Myths,” Indian Journal of Theology, Vol.38 No.1.(Serampore Theological Department, 1996). Also Don Richardson, Eternity in their Hearts (USA: Regal Books, 1981, 2005), pp.47-50.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)